Paths to Freedom

Migration is a constant topic in the news cycle, but the truth is that it’s one of the longest enduring constants of humanity. The history of migration informs a thousand tiny details in our everyday lives that we may never notice. Early hunter-gatherers followed animals, wearing down paths. Settlers followed these already worn tracks, deepening the ruts and clearing more vegetation. When roads eventually followed, many of the routes were already clear. So, consider the fact that when you drive down Main Street USA to get your coffee, you’re actually venturing down an ancient hunting trail. Let that thought add a bit of gravitas to your morning grab-and-go.

In South Florida though, the tracks are not so well worn, with generations passing over water and sand as lifestyles changed, cities grew and politics shifted. While the roots under our feet and in our blood can be traced back to pre-colonial times, profound changes occurred in Key West (and Miami) during the past hundred and fifty years. Our proximity to Cuba has been a primary catalyst.

The second half of the 1800’s was a time of significant growth and turmoil in Cuba. A series of wars demonstrated the Cuban’s desire to stretch beyond the limitations of life under colonial rule. The Ten Years War (1868-78) was the first such assertion against Spanish rule. The Little War (1879-80) and the Cuban War of Independence (1895-98) anchored the infrastructure which would, shortly thereafter, erupt into the Spanish-American War.

As is generally the case, historical movements don’t occur in a vacuum. The Cuban Labor Movement was forged from the political revolts of this era. Growing discontent with the slow march toward independence led a number of Cuban Creole workers to create the Reformist Party with hopes of progressing elements of their agenda under strict Spanish rule. The goal was to steadily instigate small changes which would ultimately redirect society and safeguard Cuban culture. Artisans led strikes and protests. In a move to galvanize its power, Spain sent Francisco de Lersundi y Hormaechea to serve as Captain General of Cuba and impose Spanish policy. His enforcement led to the prohibition of public gatherings and created a strict censure of reformist literature.

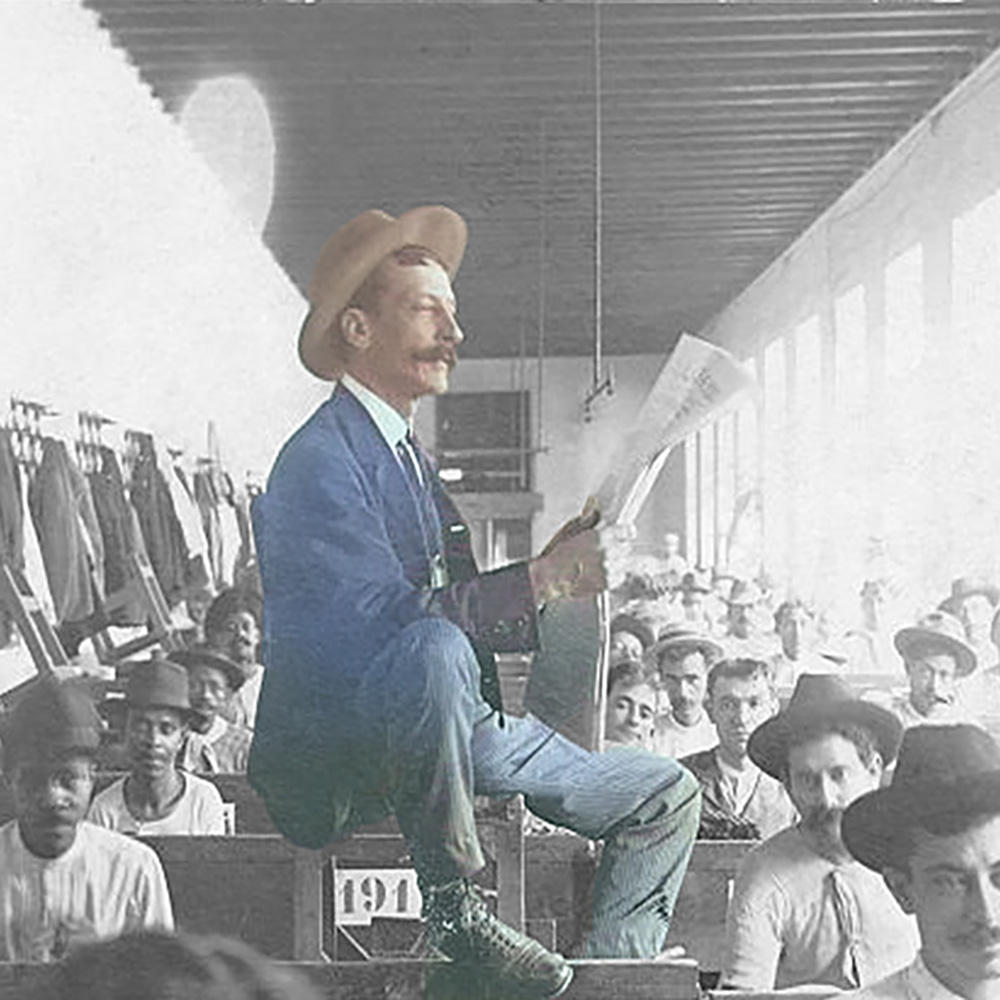

Counter to Spanish rule, the most influential figure of the reformist labor movement was not an individual, but a new-found workers’ hero and muse, La Lectura. The lecturer became a mainstay in Cuban cigar factories and in other areas of production. The role of this person was to simply read aloud to the workers while they rolled cigars. The innocuous rationale, that acquiesced to Spanish rulers, was that this ‘entertainment’ would help pass the time for the mostly illiterate population of workers and increase productivity. As the divide between laborers/artists and the ruling class grew deeper, these lectures became an easily subverted pipeline of information. Lecturas first asserted themselves by translating foreign texts and Romantic novels, feeding the workers’ desire for arts and culture. Eventually, the lecturas grew bolder and would read Labor Movement texts and calls to protest. A line was drawn.

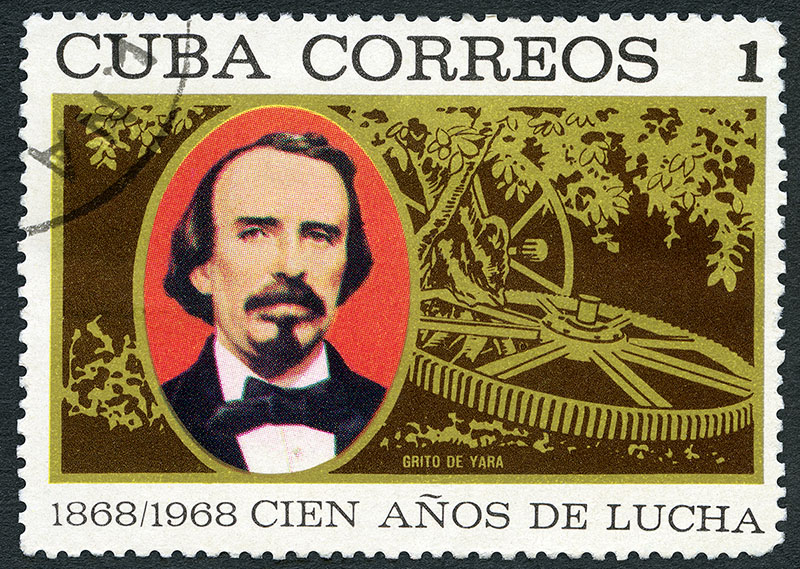

Naturally, the next stages of the reformist labor movement were more vocal and bloodier. It became apparent that quietly fighting within the system was not progressing the cause quickly enough. Poets clashed with military, fighting a bold, but losing battle. And then, above the readings of the lecturas, a battle cry rose. Literally named The Grito de Yara (Cry of Yara), the pronouncement was made by landowner Carlos Manuel de Cespedes of Yara in 1868. His declaration of independence called for enhanced rights and equity for landowners, artisans, and laborers. It also served as the first shot fired in the Ten Years War, a struggle which ultimately claimed over 200,000 lives.

Over the next thirty years, wars raged on in Cuba. Emigration from the island began years prior, in fits and bursts, as discontentment with Spanish rule had grown. But during the late 1800’s, the upheaval on Cuban soil prompted large waves of citizens to emigrate. The bulk of this mass exodus was bound for the United States, with workers and artists arriving in New York, New Orleans, Philadelphia, Miami and Key West. These immigrants came to the United States with directive, with purpose and–most consequentially to Key West’s cultural history–with diverse skill sets. Between 1868 and 1900, over 50,000 Cubans arrived in the US and navigated through the processes of immigration and naturalization. While these cigar workers, artisans, merchants and landowners spread to several regions in the US, the largest concentration naturally followed the ancient watery route across the Straits of Florida and into Key West. After all, geography is destiny.

Once in South Florida, Cuban immigrants set up businesses and settled into neighborhoods that soon bustled with new commerce and culture. In the late 1800s Cubans were arriving in Key West in regular boatloads, with jobs and stability waiting for them. By 1870, Key West had the second-highest concentration of Cuban immigrants in the US. Many worked rolling cigars, where the tradition of la lectura continued. And this new community of Cuban merchants, professionals and skilled labor became a prominent political force in Key West and constructive members of our island community.

Key West soon became an organizational center for fundraising and political strategy in the march toward Cuban independence, with both Jose Marti and Fidel Castro spending time with the Key West Cuban community developing strategy and raising money.

And so in Key West, and throughout South Florida, over the latter part of the 1800’s and into the early 1900’s, Cuban family businesses were launched, families grew, and the creative and cultural imprint of Cuban Florida deepened. The foundation has been set for future generations to arrive and feel at home, as the ancient hunting paths have become common roads to a better life.

- Paths to Freedom - January 16, 2024

- Vaughn Cochran, Saltwater Renaissance Man - August 27, 2022

She Moves Through Music

She Moves Through Music Paths to Freedom

Paths to Freedom What’s Your Intention?

What’s Your Intention? No Mic Open Mic at Andy’s Cabana

No Mic Open Mic at Andy’s Cabana