Higgs Beach Safari: Under the Sea

Higgs Beach: Safari Under the Sea

The wind has been calm for the last few days. This is good , because when the wind doesn’t blow, it doesn’t agitate the water and make it silty. One of the great joys of living in Key West is being able to get into the water within minutes from just about anywhere on the island. And being in the water is being in another world. I love waking up, finding the weather nice, and hopping on my bicycle for a quick ride to the beach for an underwater “safari.” It really doesn’t take much; a mask and fins will do quite nicely. I throw my gear into a bag, and pedal to Higgs Beach on the Atlantic side of the island.

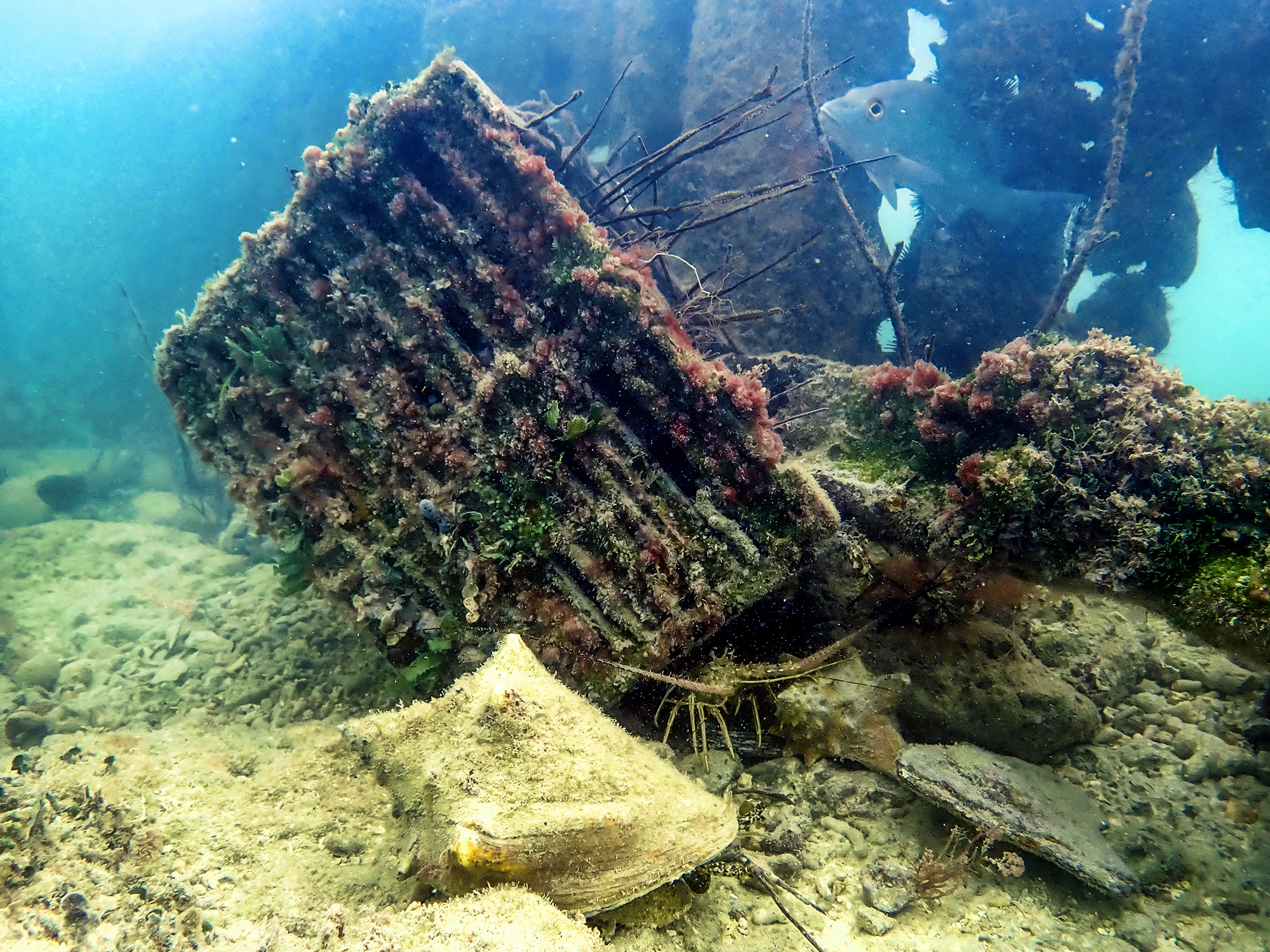

Higgs Beach is a popular spot for tourists and locals; has been for many decades. Around 1960, a breakwater made of iron panels and steel beams was installed to protect the area from the effects of the open sea. The ocean is rarely kind to man-made structures, and the Higgs breakwater is no exception: It has corroded, weakened, and as the result of time and storms, large sections collapsed into the sea. This deconstruction has been beneficial in two ways – clear water can now flow through the area and the jumble of large iron components offers protective habitat for any number of sea creatures. The old breakwater has made an unintentional artificial reef, and it is one of Key West’s better spots to easily explore the underwater world.

Higgs Beach is a popular spot for tourists and locals; has been for many decades. Around 1960, a breakwater made of iron panels and steel beams was installed to protect the area from the effects of the open sea. The ocean is rarely kind to man-made structures, and the Higgs breakwater is no exception: It has corroded, weakened, and as the result of time and storms, large sections collapsed into the sea. This deconstruction has been beneficial in two ways – clear water can now flow through the area and the jumble of large iron components offers protective habitat for any number of sea creatures. The old breakwater has made an unintentional artificial reef, and it is one of Key West’s better spots to easily explore the underwater world.

I lock my bike and make my way down the pier at the end of Reynolds Street. The slats are warm. Sea gulls give me the side eye as I pass. People on spread towels are chatting and sunning themselves. At the end of the pier, I sit on a bench, put my mask and fins on, stow my bag, and make sure my camera settings are where they should be. Then it’s down the steps and into the water.

I excuse my way through the people clustered at the bottom of the stairs, then sort of half dive into the clear water. It is cool, almost chilly, and for the first two seconds my breath goes away. I quickly acclimate to the rush, though, and the crispness becomes temperate. It is time to kick through the “swimming zone” out toward deeper water. While propelling forward, I check my camera and make sure no bubbles are in the lens. A final tug on my fin straps, and then I start looking.

My goal is straightforward but always unpredictable. I am here at Higgs Beach to take photographs of the varied marine life, but I never know what I will see. Once, I made it about 100 feet before swimming into a cloud of silt only to find that it contained a manatee at the center, pulling clumps of sea grass from the sand for breakfast. Another time, a spotted eagle ray nearly as big as me brushed by from behind, taking me by surprise (and yielding no pictures). This time, as I head out, a cloud of silversides envelops me. It is almost disorienting as many thousands of these small fish are suddenly swimming and swirling all around. I stick my camera out in front of me and shoot the mass as it speeds by. The school moves on; so do I.

There is a particularly large section of collapsed breakwater with wide steel panels resting nearly on their sides. These fallen plates have formed a cave-like environment – ideal for fish seeking an enclosed safe space, and nurse sharks are often napping in the dark underside. I grab a breath and dive down to see what might be there. There’s nothing but some unrecognizable fish backed into the murk, so I move on.

The opening in the seawall leads to the open water, and a couple hundred yards out, there is an area of rocky, hard bottom where basket sponges and thin-fingered gorgonians form a comfortable colony. These creatures are attached to the bottom and filter food from the water. As simple as their lives might be, they have beautifully contrasting forms and colors, and with the right light and angle they stand out beautifully against the blue water. With the light to my back, I spit salty water from my snorkel, take in a deep breath, go to the bottom, frame a sponge and its neighbors in the viewfinder, and pull off a few clicks before slowly returning to the surface.

With no other creatures on the horizon, I swim to the open-ocean side of the breakwater, where corals of all types have attached to the steel wall. Small, colorful fish flit around this artificial reef, while queen conchs – the mascot of the Florida Keys – graze on algae at its base. The corals, zig-zagged and pocked, are beautiful from a distance, but up close they reveal their complexity. Each coral “head” is really a community of thousands of small, individual polyps joined together on a calcareous base built by their forefathers. Each polyp has multiple, tiny tentacles with which they grab food floating by to pull into their mouths and bodies. They form an interlocked, vibrant surface. I swim down to these corals and get my camera as close as I can without touching them to shoot the polyp-level existence. This takes plenty of bobbing up and down because it isn’t easy. A steady stream of ocean waves banging against the breakwater makes it hard to hold steady, and it takes many shots to make sure that a few will achieve my goals.

The breakwater at Higgs Beach also serves a stop for man-made debris, and a few abandoned stone crab traps that drifted across the seafloor have come to rest at its base. If you squint the right way, these plastic boxes look a bit like ancient treasure chests. Though they were designed to capture and hold marine life, they are now broken and benign, and any number of creatures make the now-open containers a home.

I round the end of the breakwater to pass from the open water to the sheltered inside and what is technically the Higgs Beach swim area. It is far from shore, though, and no other swimmers are around. Here, there is a jumble of iron beams along the inside of the wall, and towards the shore a large meadow of sea grass extends as far as the eye can see. This is where my pace really slows because a careful eye will reveal details: juvenile fish hide in the tangles of grass, anemones and sea urchins sit quietly in crevices, and strange and colorful plants are everywhere. I quietly drift with the current while scanning the water from top to bottom for anything interesting, only kicking now and then to stay on course.

A large school of snappers looms ahead, congregating around a jumbled structure. They are not sure of my intentions and are skittish, so I approach very slowly. As the distance between us nears, I take a deep breath, find a handhold on the bottom, and swim down. There, I just sit quietly so the fish do not get scared and swim away from me. When everything is calm, I slowly extend my camera towards them, frame my shot, and quietly press the shutter button. It isn’t long before the feeling of my body telling me that I have used up my oxygen begins to creep over me. I don’t want to push the limits of safety, so I slowly rise to take more air. It has now been well over an hour, and though the Key West water is relatively warm, it is colder than the 98.6 degrees of human body temperature; a chill is kicking in. It is time to head back to shore.

Even though there are plenty of other places to explore and subjects to shoot, and I hate to leave them behind, it has been a good outing. I know I have taken many good and interesting photographs that capture a bit of the wonder of the underwater world. I am thankful that island life makes experiences like this so readily accessible. For now, it is time to dry off, warm up a bit in the sun, then bike back home. It will be fun to share what I saw with my family and friends.

- Higgs Beach Safari: Under the Sea - August 15, 2024

Cuzzy’s On First

Cuzzy’s On First C.H.U.B.S.

C.H.U.B.S. Conch Town Records

Conch Town Records Tall Ships And Their Masters

Tall Ships And Their Masters